offline

- Pridružio: 07 Avg 2008

- Poruke: 2528

- Gde živiš: VII kat

|

U rimskom Kapitolskom muzeju izložen je jedan od Mikelanđelovih crteža sa predstavom Bogorodice i malog Hrista. Nepostojanje direktnog kontakta između majke i deteta nameće zaključak o hladnoći i uzdržanosti majke. Ona ne gleda u dete, i nema nagoveštaja nežne i posvećene majčinske ljubavi. Ovo je tek jedno od mnogobrojnih Mikelanđelovih dela koja na sličan način predstavljaju odnos Bogorodice i Hrista. Ovakav odnos prisutan je i na jednom od Mikelanđelovih najranijih radova, reljefu sa predstavom Bogorodice na stepeništu, kao i na dosta kasnije izrađenoj Bogorodici sa malim Hristom u Mediči kapeli.

Citat:This drawing on a support made by gluing two sheets together, has often been called a “small cartoon”. However there is no evidence that this piece represents a preparatory phase of any work by Michelangelo or by artists connected to him. It is instead enlightening to think of this piece, without comparison in the corpus of Michelangelo’s drawings, as a meditation – continually recurring in the artist’s mind- on a maternity that is too painful for the mother to fully express her love for her son. It is no accident that the most notable “pentimento” on this page shows that Michelangelo had first drawn the Madonna’s face in profile, with downcast eyes looking at the Child. Here and very often elsewhere, we find reminiscences of a tradition of maternal-filial tenderness that the artist was not able to accept from his predecessors, arriving instead at a dramatic absence of communication between mother and child.

The image of the mother has a pose and an expression that are completely disconnected from The Child at her breast; her gaze is lost in the foreboding of future tragedy. In terms of the piece’s content and psychology, the youthful Michelangelo had already dealt with the enigma of this gaze in his Madonna of the Steps.

But over time the idea would evolve stylistically until it reached its highest expression in the mysterious "Madonna of the New Sacristy" in San Lorenzo, whose undeniable similarities to this drawing support the date we have accepted here.

http://www.artdaily.org/index.asp?int_sec=11&int_new=34858

Mikelanđelo Buonaroti, Bogorodica sa detetom, oko 1525.

Mikelanđelo Buonaroti, Bogorodica na stepenicama, oko 1490.

Mikelanđelo Buonaroti, Mediči Madona, 1521-31.

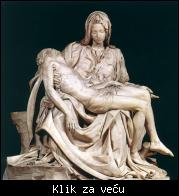

O odnosu Mikelanđela prema motivu majke pisao je između ostalih i Miloš Crnjanski. Smatrao je da je Mikelanđelo lik svoje majke, koja je umrla kada je on imao samo šest godina, upamtio, i preneo na neke od svojih skulptura. Pre svega na lik Bogorodice iz Briža kao i lik Bogorodice koja oplakuje mrtvog Hrista u crkvi Svetog Petra u Rimu. Krajnju emotivnu uzdržanost ovih Bogorodica Crnjanski smatra delom velike tajne koju je u Mikelanđelovom životu predstavljala njegova majka.

"Što se pak tiče hipoteza, meni, lično, samo se jedna čini opravdana. Odgovor na pitanje: ko je bila mati Mikelanđelova?

Zašto o njoj, i savremenici, i njihovi najbliži, biografi, i svi istoričari, do najnovijih, ponavljaju samo jedno ime, kao papagaji, i ništa više. Francesca de Neri di Miniato del Sera e di Binda Rucellai.

Meni se, čak i ti, oskudni podaci, o toj ženi čine, ne baš potvrđeni, a vrlo čudni. Uzalud sam pokušavao, preko svojih prijatelja u Fiorenci, da saznam nešto više, o toj ženi, za koju se ponavlja samo da je zapisana i knjigu mrtvih, da se udala vrlo mlada, umrla mlada. A Mikelanđela, koji je dat, odmah po rođenju, jednoj dojkinji, ženi jednog kamenoresca i ćeri jednog kamenoresca, možda nije ni videla više. Bio je navršio 12 godina kada je zabeležen prvi put, u dokumentu, u Fiorenci. Mati mu je, međutim, kažu, bila umrla još kad je bio dete. U šestoj godini.

Umrla je, kažu, istrošena porođajima. Posle 5 ili 6 porođaja. Zašto je Mikelanđelo ne pominje u svojim pismima, sem jednom po imenu, a živeo je do 90.

Zašto je njegov otac ne pominje, a stalno su u prepisci?

Zašto je braća njegova nikad ne pominju? Zašto i oni nisu davani dojkinji? Zašto ponavlja Mikelanđelo da je rođen u tami, da je njegova nesreća započela već u kolevci? Zašto pominje neki očev greh? Zašto tu ženu, koju neki biografi pišu i kao Francescu Rucellai, ne nalazimo, ni u toj, čuvenoj Fiorentinskoj porodici? Camilla Rucellai je poznata. Ta Frančeska se ne pominje. Krajnje bi vreme bilo da se vratimo toj materi Mikelanđela i da tražimo dokumenta o njoj. Ako ih ima.

Mene, lično, privlači ta tajna, oko rođenja Mikelanđelovog, zato , što se, zaista, MATI, javlja u skulpturi Mikelanđela kao GLAVNI umetnički i intelektualni problem. Pored tog napuštanja, nesavršenosti, prekida, pri izradi skoro svakog dela Mikelanđela.

...

Ja sam dugo gledao te glave tih dveju Madona, te skulpture u Rimu, i te u varoši Briž. Dugo sam gledao ta lica. I ono u Rimu i ovo u Brižu nežna su lica, tužna, devojačka. Ne znamo da li je, i kada je, Mikelanđelo počeo da upotrebljava žive modele. U Fiorenci, ako je verovati Kondiviju, a ne treba verovati biografima, crtao je model iz glave, iz sećanja, perom isprva, a posle, docnije, crvenim kredama. Ja mislim da su ove dve madone, ista žena - ista zamisao - možda i sećanje, na mater.

Vrlo su mlade, a obe Fiorentinke, snažnih nogu i naglašenih grudi. Ista su čela i kosa na čelu, iste su oči, samo su u Rimu isplakane, a u varoši Briž oči mlade matere, koja je zabrinuta. Isti je čisti, vanredni nos, ista nežna devojačka usta, samo su u Rimu gorka, a ova u Brižu napućena od ponosa. Ista je i brada, samovoljna. Oba su lica Mikelanđelu dobro poznata, pa idealisana.

...

Šta sam našao, pita me domaćinova ćerka, podrugljivo?

Markezanu di Peskara, koju je ostareli Mikelanđelo obožavao?

Vidim kako me njen otac gleda namršten.

Ne, nego mater Mikelanđelovu, kažem, o kojoj ništa ne znamo. Sudbinu koja počinje u materi već pre rođenja. Kamen Sizifov koji posle gura uzbrdo i nizbrdo, celog veka, do smrti, na kraju. Pod utiskom sam onoga, rekao sam već, što je doktor Frojd o Leonardu napisao. Pitam se šta bi o Mikelanđelu pisao da se o materi Mikelanđelovoj pitao.

Domaćin onda namrgođen kaže da mu nije jasno kud ciljam sa tim, stalnim, pitanjima o materi Mikelanđelovoj. Uopšte preterujem davanjem tolikog značaja porodičnom životu u radu tih velikih ljudi italijanske renesanse. Mati, u našem životu, igra, priznaje, jednu vrlo lepu ulogu, ali ne toliko, toliko sudbonosnu. Ono što se u porodičnom životu događa, poznato je davno, ponavlja se uvek isto i nije neobično. Neobično se događa u našem životu u spoljnom svetu. O tom da govorimo."

Miloš Crnjanski, Knjiga o Mikelanđelu

Mikelanđelo Buonaroti, Pieta, crkva svetog Petra u Rimu, 1499.

Mikelanđelo Buonaroti, Bogorodica iz Briža, 1505.

Mikelanđelo Buonaroti, Pieta, crkva svetog Petra u Rimu, detalj.

Mikelanđelo Buonaroti, Bogorodica iz Briža, detalj.

Zanimljivo je uporediti ovaj književni pristup Mikelanđelovom delu sa pristupom jednog istoričara umetnosti. Džon Poup-Henesi autor je obimnog dela o italijanskoj skulpturi. Pišući o Mikelanđelu, Poup-Henesi dovodi u vezu upravo iste dve skulpture kao i Miloš Crnjanski. Poup-Henesi naglašava najpre u kojoj meri je tema piete bila neuobičajena među italijanskim skulpturama petnaestog veka, i u kojoj meri je Mikelanđelo tu temu transponovao u sferu ličnog religioznog promišljanja. Na isti način pristupio je Mikelanđelo i temi Bogorodice sa malim Hristom, koja od intimne, porodične predstave postaje delo koje izražava umetnikovo shvatanje centralne tragične teme hrišćanstva na nov, monumentalan način. Za razliku od Crnjanskog, Poup-Henesi sebi ne dopušta luksuz izvođenja zaključaka na osnovu ličnih impresija, već to čini na osnovu poznavanja ikonografije umetnosti Mikelanđelove epohe. Iako su im polazišta sasvim različita, i Poup-Henesi i Crnjanski dolaze do istog zaključka, o postojanju jedinstvenih i krajnje ličnih motiva koji su rukovodili Mikelanđelovim umetničkim stvaralaštvom. I dok je za Crnjanskog od suštinske važnosti predstavljao problem otkrića koji su to motivi bili, za Poup-Henesija je najvažnije bilo argumentovano dokazati kako su ti motivi transformisali postojeću umetničku tradiciju i uticali na formiranje stila visoke renesanse u skulpturi.

"In 1498, in Rome, Michelangelo received his first commission for a major religious sculpture. There resulted one of his most famous works, the St Peter's Pieta. We are prone to take the Pieta for granted, as we do all the greatest works of art, but if we could contrive for a moment to see it with fresh eyes, we should find it an entirely inexplicable sculpture on the counts of style, subject and typology. No large marble Pieta was carved anywhere in Italy in the whole fifteenth century, but in Florence about 1490 the subject became popular in painted altarpieces. The altarpieces are, however, self-contained - they show the Virgin mourning over the dead Christ - whereas the sculptured group is not - it shows the Virgin displaying the dead Christ to the onlooker. That this is the subject of the group is left in no doubt by the Virgin's extended hand, part of which has been restored, but where everything save possibly the index finger is in the position Michelangelo designed. The Virgin is a youthful figure. Many years later Michelangelo defended this break with conventional iconography, but it was not universally acceptable, and when a copy of the group was made for Genoa by Michelangelo's onetime assistant Montorsoli, this aspect of its imagery was modified.

The group is constructed with great deliberation as a pyramid. Christ's head is turned back in such a way as not to break the bounding line, and beneath his body the folds of the Virgin's cloak flood down like a waterfall. In the sculpture of the fifteenth century there is no motif at all like this, and for that reason parallels have been sought in the North among German Vesperbildern and French sculptured Pietas. The group was commissioned by a Frenchman, Cardinal Jean Villier de la Grolaie, who came from Auch and had been Abbot of St Denis, so it is not impossible that it was planned with a French Pieta in mind. But to admit that (and it is far from certain) is to recognize the transformation that has taken place. The jagged drapery has been rounded and ordered and filled out, a Hellenistic hero has been substituted for the doll-like Christ, and the emotion on the Virgin's face is rendered with supremely classical restraint.

The Pieta can only have resulted from close intellectual application, but we have no way of reconstructing the ideas the sculptor sifted and dismissed. Some impression of the nature of his thought can none the less be gained from the only other work he produced of the same kind. This is the Virgin and Child at Bruges, which was carved after he returned to Florence, probably in 1504 or 1505. Here, thanks to the survival of a number of preliminary drawings, we can watch Michelangelo's creative machinery at work. In what is presumably the earliest of the drawings, the Child is not shown standing, as in the completed group, but is supported on the Virgin's knee, with his head turned in right profile and his right leg outstreched. The Virgin in this version, like so many of her predecessors in the fifteenth century, is gazing down, and her feet, like the feet of so many fifteenth century Madonnas, are set flat on the base. In another study the scheme is modified; the left foot of the Virgin is set higher than her right, and the Child stands between her legs. In a third sketch on the same sheet the relative positions of the two feet of the Virgin are preserved, but like the Child is shown standing in front of her right knee, while in a fourth sketch, in the British Museum, the Virgin gazes dispassionately outwards, as she does in the completed group. These preliminary drawings register a change of concept as well as form. The maternal motif on which fifteenth century Madonnas almost without exception had been founded is progressively abandoned, and the resulting statue has the same relation to traditional Virgin and Child groups that the Pieta has to the traditional Mouring over the Dead Christ. In both the narrative element has been excised, and the Virgin is shown with her features frozen by suffering or by premonition, offering to the spectator the dead or living Christ. The effect is so meditated and withdrawn that at first sight we may be tempted to describe it as impersonal, but these are in fact the first examples of the highly personalized religious iconography which was to reach its climax in Michelangelo's later works.

John Pope-Hennessy, Italian High Renaissance and Baroque Sculpture

|